Aquí Pedro Bellora en un video reciente explica la focalización que explicaba en #137 . Qué casualidad!!!!

Elementos para la improvisación

OFERTAS Ver todas

-

-20%IK Multimedia ToneX One Joe Satriani Ltd Ed.

-

-41%Fishman Rare Earth Single Coil PRO‑REP‑101

-

-20%tc electronic Hall of Fame 2

La verdad que es bastante más estudiable y practicable....

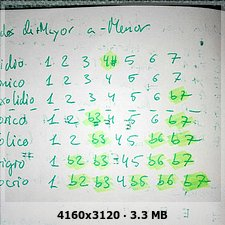

Como que esta mas claro cuales son los mayores y menores, y cuales ➕ mayores y ➖ menores.

El otro día no lo vi claro. Y hoy, mirando, he pensado esto se puede ordenar mejor, he empezado, pero lo he dejado y al entrar aquí, tate, hagase la luz, graciasss.

Por suerte mi vecino es pianista y hemos pasado el confinamiento en contacto y he podido tocar mucho con él. Hoy hemos estado mirando para arreglar un tema de Mal Waldron llamado "All Alone" con la española y el piano. La canción me ha conmovido profundamente y os la quería compartir.

Y un LP que también escuché hace un rato. Jazz del duro de verdad y sin concesión ninguna.

Y un LP que también escuché hace un rato. Jazz del duro de verdad y sin concesión ninguna.

#151 Gracias por la aportación astrako, me ha gustado mucho escucharlos (y oye, vaya potra tener un vecino así en cuarentena..). Conocía el nombre del pianista, pero no estoy seguro de haber escuchado nada suyo, o al menos como líder de la sesión.. seguro que de acompañante le he oído muchas veces.

Excelente también el primer post y la idea del hilo en general. Estoy muy de acuerdo con tu línea de pensamiento respecto al tema de la improvisación en general y pienso leerme el hilo entero en cuanto pueda dedicarle un rato.

Quería hacer una pequeña aportación complementaria. Es un post copiado del usuario "Dasein" en el foro Jazzguitar.be y obviamente no es mi autoría. Lo escribió hace unos años y, aunque sólo es un enfoque o una de las prácticas que puedes llevar a cabo para aprender improvisación, SIEMPRE en conjunción con otros aspectos, me parece muy, muy interesante. Por cierto, no sólo limitado al jazz, aunque en este caso se refiera al jazz.

Si alguien tiene problemas con el inglés o pasándolo por un traductor y/o hay suficiente gente interesada, lo traduzco en un momento y re-subo. Cantar amigos, todo es cantar.

dasein escribió:

in trying to learn how to learn jazz, the temptation is to think that "the secret" that prevents us from reaching the heights of the masters is always "somewhere else"

we spend countless amounts of money on books, videos, lessons hoping that somewhere along the way, we will acquire that knowledge that will bridge the gap, so to speak.

it's not that books never help (although ironically, the books that really CAN help like The Advancing Guitarist are the books many players tend to avoid working on, since the payoff is not immediate and requires extensive time and effort). but there is always the sense that these books are incomplete.

this is further highlighted by the fact that the great players that learned to play before the 1970's had NO access to the wealth of instructional materials that we had, yet their playing is still light years ahead of us.

it could be that these players were all "geniuses" who could figure this all out. possibly, but there's no real evidence of that. they could also be players who just practiced 12 hours a day and just worked harder at it than us. also possible, but for every player like Charlie Parker or Coltrane who practiced 12 hours a day, there are stories of musicians who decidedly did NOT have fanatical practice schedules.

i would argue that there is something else that we're missing, something that we missed not because it was a secret, but because it was right in front of us the whole time.

if you read lots of different musician's biographies and interviews, you will notice something that comes up an awful lot:

"When I was younger, I really went crazy over X RECORDING... I practically wore out the grooves on it."

many, many examples of this throughout jazz history:

- Charlie Parker was an obsessive Lester Young fan, and there are bootleg recordings of him playing famous Prez solos like "Shoeshine Boy" as a warmup, note-for-note

- Wes Montgomery started playing guitar because of Charlie Christian, and learned how to play by copying his solos. the first time Wes went onto a bandstand, he got so nervous when it came time to solo that he just played a Charlie Christian solo note-for-note

- Sonny Rollins, when he first came up, was notable for sounding almost EXACTLY like Coleman Hawkins until he went and shed his bebop stuff

- Pat Metheny would talk about interviews about how he would listen to a handful of recordings over and over again until he had them memorized (I believe they included Wes' Smokin at the Half Note and Miles Davis' Four and More)

furthermore, you have Lennie Tristano where a HUGE part of his pedagogy, the thing he called his "most important contribution to teaching", was to have his students sing along to famous solos and then play them on their instruments.

it is tempting to look at all this, and think that the key is just to transcribe more, to learn more solos. but it is much deeper than that.

it's not enough to just be able to play along with a solo, because then you can turn it into a lifeless technical exercise. you must absorbthe solo, be able to sing it from memory effortlessly and then play it on your instrument.

we hear all the time that "jazz is a language." what does that really mean? does it mean that we can just learn lots of phrases (licks) and be able to speak it? if that was the case, all we would need to be a great jazz player is one of those 1001 Jazz Lick books.

but i would strongly argue that jazz as a language is much, much more than just a set of licks. in order to play jazz, you need more than just lines. there is an essential rhythmic foundation, requiring an intuitive knowledge of proper accents and syncopation. there is not just the lines themselves, but the way the lines interact with the song both harmonically and rhythmically. there are the melodic shapes that organize the lines. there's phrasing. all of these things are essential.

there's simply no way you can improvise on a high level without these things. there's also no way you can improvise on a high level if you have to THINK about these things on a conscious level, anymore than you can speak a language eloquently if you're thinking about syntax, verb forms, or grammar.

all these things must be ingrained into your unconscious mind, and the best way to get it there is through focused and intensive listening.

with me so far? alright, because here's perhaps a more controversial statement: i believe that the best place to start with this listening is with the great players that immediately preceded bebop.

i'm not alone on this, since Lennie Tristano would start almost all his students with Lester Young. but here's my reasoning:

- bebop, while a essential to the jazz language since 1940, is simply too complicated for a beginning musician to hear and absorb. the tempos are too fast, the melodic and rhythmic ideas are too complex.

- the players immediately preceding bebop are much easier to hear and absorb on every level. and because they directly inspired the bebop players, absorbing their playing will make later bebop study much, much easier.

which players would i start with? i would go with the following:

- Lester Young. I would stick with mostly the pre-war stuff. it's the music that bebop players would have studied, and it's Young at his most effortless. anything with the Basie band or his collaborations with Billie Holiday are gold. don't forget his famous session with Basie's small group with "Lady Be Good" or "Shoeshine Boy." countless players learned those solos note for note.

- Charlie Christian. shouldn't have to explain this one. the old compilation "The Genius of the Electric Guitar" works great

- Coleman Hawkins. lots of great choices here... Body and Soul... The Man I Love... the Tristano school players did not like the Hawk compared to Lester Young, but the fact that Lee Konitz STILL learned a bunch of is solos should speak volumes

- Roy Eldridge. there's an old Columbia compilation with the Gene Krupa band that has loads of great stuff to learn. there's also lots of cuts out there where he's a sideman for a vocalist... one of my favorites is his solo on "Nobody's Baby" with Mildred Bailey

- Ben Webster. anything from the Blanton/Webster band is great, but i would especially learn his famous solo on "Cottontail." any solo that's so famous that audiences demand it be repeated ad nauseum every time they play the song... yea, that's probably a pretty good solo

now, you may notice that i left out some fairly obvious pre-bob players. what about Louis Armstrong? Sidney Bechet? seriously, what about Louis Freakin' Armstrong, isn't he the most important player in the history of jazz?

you're more than welcome to give the same treatment to Satchmo. but remember how we skipped the bebop players for now because it was too complex? Louis Armstrong's note choice and melodic ideas aren't that complex, but his rhythmic ideas and time feel were from a completely different planet. listen to a bunch of solos from the Hot Fives and Sevens and you'll see what i mean. he is definitely worth studying, but for te beginning player, i would recommend coming back to him later

so how do you put this into practice? like so...

1. first, get the music i recommended above. many of these can be had for dirt cheap on Amazon or iTunes.

2. next, rip them onto your computer and open them in a program like Audacity. take each song, and cut out everything EXCEPT the solo. export them as new MP3s so you're left with a bunch of audio tracks of JUST solos. the nice thing about these pre-bop recordings is that the solos are usually well under a minute each.

3. put these solo tracks on an MP3 player, your phone, burn them onto a CD, whatever. now you must listen to them CONSTANTLY. put them on a loop, and just let it play over and over. play them in the car. play them on the bus. play them as you're jogging. play them while you're at work. play them as you're getting ready to fall asleep. play them until you're sick of them. OVER AND OVER again.

4. after countless listens over weeks and months, you're eventually going to start memorizing these solos. first see if you can sing along with them. once that happens, you can start learning them on your instrument. you'll be surprised at how easy it is once you go through all this.

after you do that, i would move on and do the same thing to bebop players: Bird, Diz, Bud Powell, Fats Navarro, etc.

if you do this thoroughly, i guarantee you that it will have a transformative effect on the way you play and hear this music. when you're able to clearly hear and understand bebop, it changes how you hear ALL of jazz that came after it.

obviously, you should still work on other things: scales, chords, arpeggios, voice leading, learning tunes, all that fun stuff. but in working with my students, i find that this sort of intensive listening and absorbtion is often a "missing piece" in their playing

Excelente también el primer post y la idea del hilo en general. Estoy muy de acuerdo con tu línea de pensamiento respecto al tema de la improvisación en general y pienso leerme el hilo entero en cuanto pueda dedicarle un rato.

Quería hacer una pequeña aportación complementaria. Es un post copiado del usuario "Dasein" en el foro Jazzguitar.be y obviamente no es mi autoría. Lo escribió hace unos años y, aunque sólo es un enfoque o una de las prácticas que puedes llevar a cabo para aprender improvisación, SIEMPRE en conjunción con otros aspectos, me parece muy, muy interesante. Por cierto, no sólo limitado al jazz, aunque en este caso se refiera al jazz.

Si alguien tiene problemas con el inglés o pasándolo por un traductor y/o hay suficiente gente interesada, lo traduzco en un momento y re-subo. Cantar amigos, todo es cantar.

dasein escribió:

in trying to learn how to learn jazz, the temptation is to think that "the secret" that prevents us from reaching the heights of the masters is always "somewhere else"

we spend countless amounts of money on books, videos, lessons hoping that somewhere along the way, we will acquire that knowledge that will bridge the gap, so to speak.

it's not that books never help (although ironically, the books that really CAN help like The Advancing Guitarist are the books many players tend to avoid working on, since the payoff is not immediate and requires extensive time and effort). but there is always the sense that these books are incomplete.

this is further highlighted by the fact that the great players that learned to play before the 1970's had NO access to the wealth of instructional materials that we had, yet their playing is still light years ahead of us.

it could be that these players were all "geniuses" who could figure this all out. possibly, but there's no real evidence of that. they could also be players who just practiced 12 hours a day and just worked harder at it than us. also possible, but for every player like Charlie Parker or Coltrane who practiced 12 hours a day, there are stories of musicians who decidedly did NOT have fanatical practice schedules.

i would argue that there is something else that we're missing, something that we missed not because it was a secret, but because it was right in front of us the whole time.

if you read lots of different musician's biographies and interviews, you will notice something that comes up an awful lot:

"When I was younger, I really went crazy over X RECORDING... I practically wore out the grooves on it."

many, many examples of this throughout jazz history:

- Charlie Parker was an obsessive Lester Young fan, and there are bootleg recordings of him playing famous Prez solos like "Shoeshine Boy" as a warmup, note-for-note

- Wes Montgomery started playing guitar because of Charlie Christian, and learned how to play by copying his solos. the first time Wes went onto a bandstand, he got so nervous when it came time to solo that he just played a Charlie Christian solo note-for-note

- Sonny Rollins, when he first came up, was notable for sounding almost EXACTLY like Coleman Hawkins until he went and shed his bebop stuff

- Pat Metheny would talk about interviews about how he would listen to a handful of recordings over and over again until he had them memorized (I believe they included Wes' Smokin at the Half Note and Miles Davis' Four and More)

furthermore, you have Lennie Tristano where a HUGE part of his pedagogy, the thing he called his "most important contribution to teaching", was to have his students sing along to famous solos and then play them on their instruments.

it is tempting to look at all this, and think that the key is just to transcribe more, to learn more solos. but it is much deeper than that.

it's not enough to just be able to play along with a solo, because then you can turn it into a lifeless technical exercise. you must absorbthe solo, be able to sing it from memory effortlessly and then play it on your instrument.

we hear all the time that "jazz is a language." what does that really mean? does it mean that we can just learn lots of phrases (licks) and be able to speak it? if that was the case, all we would need to be a great jazz player is one of those 1001 Jazz Lick books.

but i would strongly argue that jazz as a language is much, much more than just a set of licks. in order to play jazz, you need more than just lines. there is an essential rhythmic foundation, requiring an intuitive knowledge of proper accents and syncopation. there is not just the lines themselves, but the way the lines interact with the song both harmonically and rhythmically. there are the melodic shapes that organize the lines. there's phrasing. all of these things are essential.

there's simply no way you can improvise on a high level without these things. there's also no way you can improvise on a high level if you have to THINK about these things on a conscious level, anymore than you can speak a language eloquently if you're thinking about syntax, verb forms, or grammar.

all these things must be ingrained into your unconscious mind, and the best way to get it there is through focused and intensive listening.

with me so far? alright, because here's perhaps a more controversial statement: i believe that the best place to start with this listening is with the great players that immediately preceded bebop.

i'm not alone on this, since Lennie Tristano would start almost all his students with Lester Young. but here's my reasoning:

- bebop, while a essential to the jazz language since 1940, is simply too complicated for a beginning musician to hear and absorb. the tempos are too fast, the melodic and rhythmic ideas are too complex.

- the players immediately preceding bebop are much easier to hear and absorb on every level. and because they directly inspired the bebop players, absorbing their playing will make later bebop study much, much easier.

which players would i start with? i would go with the following:

- Lester Young. I would stick with mostly the pre-war stuff. it's the music that bebop players would have studied, and it's Young at his most effortless. anything with the Basie band or his collaborations with Billie Holiday are gold. don't forget his famous session with Basie's small group with "Lady Be Good" or "Shoeshine Boy." countless players learned those solos note for note.

- Charlie Christian. shouldn't have to explain this one. the old compilation "The Genius of the Electric Guitar" works great

- Coleman Hawkins. lots of great choices here... Body and Soul... The Man I Love... the Tristano school players did not like the Hawk compared to Lester Young, but the fact that Lee Konitz STILL learned a bunch of is solos should speak volumes

- Roy Eldridge. there's an old Columbia compilation with the Gene Krupa band that has loads of great stuff to learn. there's also lots of cuts out there where he's a sideman for a vocalist... one of my favorites is his solo on "Nobody's Baby" with Mildred Bailey

- Ben Webster. anything from the Blanton/Webster band is great, but i would especially learn his famous solo on "Cottontail." any solo that's so famous that audiences demand it be repeated ad nauseum every time they play the song... yea, that's probably a pretty good solo

now, you may notice that i left out some fairly obvious pre-bob players. what about Louis Armstrong? Sidney Bechet? seriously, what about Louis Freakin' Armstrong, isn't he the most important player in the history of jazz?

you're more than welcome to give the same treatment to Satchmo. but remember how we skipped the bebop players for now because it was too complex? Louis Armstrong's note choice and melodic ideas aren't that complex, but his rhythmic ideas and time feel were from a completely different planet. listen to a bunch of solos from the Hot Fives and Sevens and you'll see what i mean. he is definitely worth studying, but for te beginning player, i would recommend coming back to him later

so how do you put this into practice? like so...

1. first, get the music i recommended above. many of these can be had for dirt cheap on Amazon or iTunes.

2. next, rip them onto your computer and open them in a program like Audacity. take each song, and cut out everything EXCEPT the solo. export them as new MP3s so you're left with a bunch of audio tracks of JUST solos. the nice thing about these pre-bop recordings is that the solos are usually well under a minute each.

3. put these solo tracks on an MP3 player, your phone, burn them onto a CD, whatever. now you must listen to them CONSTANTLY. put them on a loop, and just let it play over and over. play them in the car. play them on the bus. play them as you're jogging. play them while you're at work. play them as you're getting ready to fall asleep. play them until you're sick of them. OVER AND OVER again.

4. after countless listens over weeks and months, you're eventually going to start memorizing these solos. first see if you can sing along with them. once that happens, you can start learning them on your instrument. you'll be surprised at how easy it is once you go through all this.

after you do that, i would move on and do the same thing to bebop players: Bird, Diz, Bud Powell, Fats Navarro, etc.

if you do this thoroughly, i guarantee you that it will have a transformative effect on the way you play and hear this music. when you're able to clearly hear and understand bebop, it changes how you hear ALL of jazz that came after it.

obviously, you should still work on other things: scales, chords, arpeggios, voice leading, learning tunes, all that fun stuff. but in working with my students, i find that this sort of intensive listening and absorbtion is often a "missing piece" in their playing

#152 Hola Pink, bienvenido al hilo. Muchísimas gracias por pasarte y aportar y por el artículo. Espero poder leerlo mañana.

Mal Waldron. No era un pianista de muchas florituras pero te deja clavado. Este último enlace que colgué con Steve Lacy es un disco de jazz descarnado como él solo. Te aseguro que son 84 minutos muy bien invertidos: los primeros 42 son la primera escucha, y los otros 42 porque vas a querer volver a escucharlo desde el principio. También te recomiendo que leas en internet sobre su vida. Sufrió un colapso y se olvidó de quien era y de cómo era su mundo y también de tocar el piano. Tuvo que reaprender desde el principio escuchando sus propios discos.

Pink escribió:Conocía el nombre del pianista, pero no estoy seguro de haber escuchado nada suyo, o al menos como líder de la sesión.. seguro que de acompañante le he oído muchas veces.

Mal Waldron. No era un pianista de muchas florituras pero te deja clavado. Este último enlace que colgué con Steve Lacy es un disco de jazz descarnado como él solo. Te aseguro que son 84 minutos muy bien invertidos: los primeros 42 son la primera escucha, y los otros 42 porque vas a querer volver a escucharlo desde el principio. También te recomiendo que leas en internet sobre su vida. Sufrió un colapso y se olvidó de quien era y de cómo era su mundo y también de tocar el piano. Tuvo que reaprender desde el principio escuchando sus propios discos.

#152 Acabo de leer el artículo. Transcribe o saca de oído, aprende canciones, tócalas y vencerás. La pega del artículo es que no da cuenta de que había también músicos del género que, a pesar de basar su aprendizaje en la transcripción y el conocimiento de su legado cultural, contaban con amplios conocimientos de teoría musical como Miles Davis, Gillespie, Bill Evans o Oscar Peterson. Creo que cada uno debe seguir su propio camino. Si tu objetivo es hacer música a través de la guitarra, debes buscarte la forma que mejor te vaya para conseguirlo en consonancia con tu situación personal y los medios y tiempo del que dispongas.

Pink escribió:obviously, you should still work on other things: scales, chords, arpeggios, voice leading, learning tunes, all that fun stuff. but in working with my students, i find that this sort of intensive listening and absorbtion is often a "missing piece" in their playing

Me retracto del anterior comentario. Acabo de leer el artículo más detenidamente y no había recaído en la última frase. Pues sí, escuchar exhaustivamente, sacar de oído y aprender solos y canciones de memoria es una inmejorable rutina.

Nuevo post

Regístrate o identifícate para poder postear en este hilo

justo hoy, mirandolos en un papel, he pensado en ordenarlos segun las alteraciones.... Y era esto lo que comentabas antes si señor.

justo hoy, mirandolos en un papel, he pensado en ordenarlos segun las alteraciones.... Y era esto lo que comentabas antes si señor.